Shaping Health Locally Based on Principles Gathered Globally

By Susan Mende, senior program officer, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey, USA

At the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), we believe that good ideas have no borders. This is why, as the largest philanthropy in the United States focused solely on improving health and health care, we actively search the globe for the best ways to advance health in local communities. We want to learn from the most effective health-related programs, policies, and approaches used in other countries and adapt them to use here at home—and also share with other countries the best practices we have identified in the U.S. Our ultimate goal is to build, with our many diverse partners, a Culture of Health in America, where everyone—no matter who they are, where they live, or how much money they make—has the opportunity to live their healthiest life.

One of the “best practices” we’ve been exploring globally in recent years is authentic and meaningful social power and participation in local health care systems. This is the “nothing about us without us” approach to health improvement that recognises a fundamental truth: to truly and sustainably improve the health of an entire community—to build a Culture of Health—all of its members, especially those who are the most marginalised, must have a seat at the table and a respected voice in the discussion whenever decisions are made about health and health care.

Why are social power and participation so fundamental to health and health care? According to population health researcher Dr. Rene Loewenson, director of the Training and Research Support Centre (TARSC): “When people are left out of the decision-making processes and other conversations around health and health care, unfair differences are produced between those who have the power to speak and be heard and those who do not—differences in their knowledge and understanding of health and health care, in their access to care, in their opportunities to be healthy, in their health status, and more. Inclusive processes that promote social power and participation across all community members seek to challenge the exclusive power dynamics that lead to social injustice and inequities in health, and to enhance peoples’ collective power to produce changes that support their health.”

In the U.S., we often talk about this in terms of “community engagement” around health, but despite many bright spots, engagement usually doesn’t go beyond institutions and organizations exercising their power to invite community members to join pre-planned or already existing efforts to improve health. Too often in the U.S., power is not shared equitably and community engagement is neither authentic nor meaningful for residents; too often we only pay lip service to the concept of participation and then wonder why we haven’t moved the needle on local health outcomes. Thus, my RWJF colleagues and I set out to learn more about successful practices used in other countries to build true social power and participation in health—practices that are creating healthier people and communities—and share them broadly.

Initiative Identifies, Examines International Examples

In 2016, we began working with Dr. Loewenson and a TARSC-led initiative called Shaping Health to identify and examine successful examples of social participation in health from which we could learn. Dr. Loewenson and her colleagues identified specific local examples in 12 different countries—Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Ecuador, India, Kenya, New Zealand, Scotland, Slovenia, Vanuatu, and Zambia—where great strides in partnering with residents around health and well-being have been made. In these places, residents are partners—along with doctors, nurses, social and other outreach workers, policymakers, teachers, advocates, environmentalists, and many other community leaders—in their own health and the health of their families, friends, co-workers, and neighbours. In these communities, though the details and degree of participation differ, these myriad groups and sectors work together to identify and prioritise health needs and determine how best to address those needs.

To understand how social power and participation in health are built in different places by different people using different approaches, below are brief summaries of three of the 12 examples identified and examined by TARSC. In actuality, all 12 examples are quite sophisticated and complex in their approaches and far more detailed descriptions are available in case study form on the Shaping Health website.

- In Chile, where health is considered a human right, citizens are expected to participate in shaping the ways that the nation’s decentralised public health system identifies, prioritises, and addresses health care needs at all levels—national, regional, and local. At each of these levels, residents—including people with disabilities, immigrants, and other marginalised groups—are considered “co-participants” in decision-making and action around health. Thus, there are myriad opportunities for Chileans to exercise their social power in health. Even so, residents do not always feel listened to by their health institutions, some of which need to a better job of fulfilling their commitments to their communities. When a local health agency in Santiago, for example, saw a need for a manual on adolescent sexuality, it handed development of the manual over to a committee of teens from six schools across the city to determine content and design. The manual generated significant public controversy for its frank and uncensored language but, because the health agency recognised early that the teens would bring their own lived experiences to the manual, giving it an authentic voice, it proved popular and useful among the young people who needed to read it.

- In New Zealand, on the North Island’s east coast, local residents’ connections to their Maori roots run deep, but many in this low-income region struggle to maintain their health. They are supported in their health-related efforts by the Ngāti Porou Hauora (NPH) health agency. NPH is owned and managed by the local community; is a major employer in the region; and adheres to the Maori concept that people don’t merely receive health services, but also have the right to participate in and control their own health and health care. At the same time, NPH is an active community member with health workers who live in and are recruited from the area they serve, making regular home visits and participating in community gatherings. NPH participatory practices are flexible and based on values shared with the community, such as honesty and transparency. Despite many challenges, NPH delivers more services than most other health agencies in New Zealand—at times outperforming on breast cancer screenings, immunisations for two-year-olds, and cardiovascular disease risk assessments. NPH’s success suggests that participation flourishes when it is founded on the community’s own culture rather than only as a functional need of the health service.

- In Zambia, the Lusaka District Health Office has been using social participation to strengthen local primary care for more than 10 years. Working together, community members, health workers, and people from sectors outside of health have built trusting relationships and found a variety of innovative ways to promote community health and well-being. For example, residents and health workers are taught to use cameras to document issues of concern in the community. They call this activity “Photo Voice.” The photos—such as one of a blocked sewer that created unsanitary conditions or of a sick person on a bike who had no other way to get to the hospital—stimulate community-wide discussions around the very human issues depicted. The health office also holds health literacy workshops as another way of bringing residents’ voices into discussions about local health initiatives and services. Following the workshops, health literacy facilitators support community meetings that help residents and health workers better understand each other’s perspectives and find common ground on which to work together. The workshops and community meetings have contributed to resolving local health challenges, such as a reduction in the number of cholera outbreaks in the community.

Principles that Shape Social Power and Participation in Health

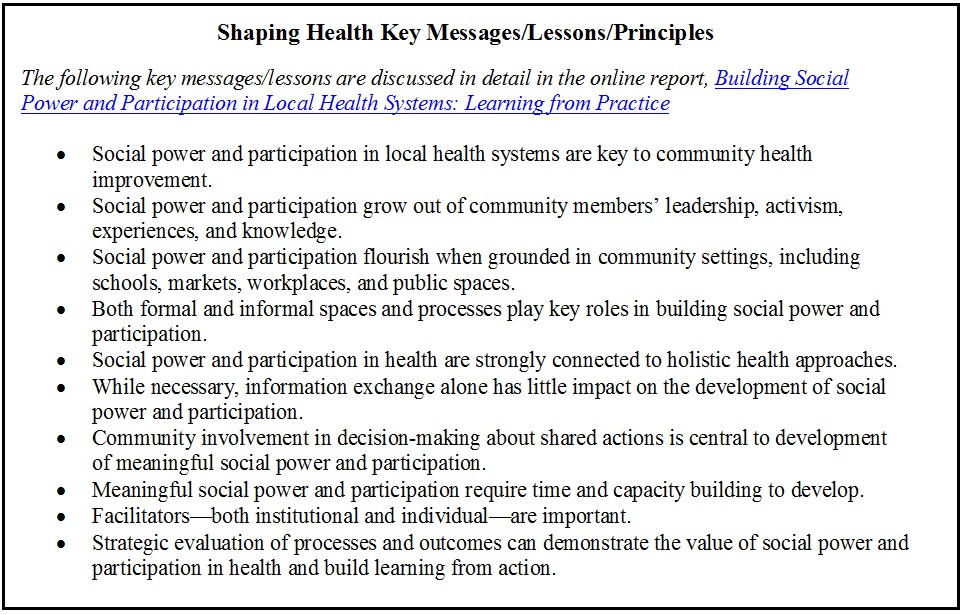

Once the 12 Shaping Health case studies had been developed, Loewenson and her colleagues from each of the 12 case study countries looked across them and identified a set of principles or lessons about building social power and participation in health that could be shared widely (see box). These included observations regarding: attitudes toward social power and participation (that they are acknowledged as key to health improvement); where and how social power and participation are best nurtured (in community-based settings); and about the commitment of resources required for meaningful social power and participation in health to take root and blossom (including investments of time, leadership, management, and other capacities, not necessarily financial).

“It’s very important for people engaged in this work to understand that the key messages or lessons are not steps that must be followed in a particular order,” said Loewenson. “There is no easy recipe for success. Instead, the key messages communicate what we have learned so far about the practices, processes, and approaches that help social power and participation in health to thrive—these are common principles gathered from across diverse countries and people.”

“It’s very important for people engaged in this work to understand that the key messages or lessons are not steps that must be followed in a particular order,” said Loewenson. “There is no easy recipe for success. Instead, the key messages communicate what we have learned so far about the practices, processes, and approaches that help social power and participation in health to thrive—these are common principles gathered from across diverse countries and people.”

International Examples and Global Lessons Inform U.S. Efforts

In addition to the 12 example communities, five U.S. sites—identified because they demonstrated a strong interest in building meaningful and authentic social power and participation in health—were also part of the Shaping Health initiative. They were: Athens City-County Health Department in Ohio; Blueprint for Health in Vermont; Centro Savila in New Mexico; 11th Street Family Health Services in Pennsylvania; and PIH Health in California.

In 2016 and 2017, TARSC and Shaping Health convened representatives from the five U.S. sites—twice in person as part of other international meetings as well as many times online—with representatives from the 12 international efforts to share information and learn from each other. At the first meeting, they worked toward developing a common language for their exchanges, arriving at shared a conceptual understanding of social participation in health. While the 12 international programs shared their experiences for the benefit of the U.S. sites, they also gained knowledge as the U.S. sites began discussing ways to adapt at home what they were learning from their international colleagues.

For example, in Southern California, PIH Health—a regional nonprofit health care delivery network serving more than two million residents across Los Angeles and Orange counties—learned valuable lessons about social power and participation from Shaping Health. Every year, as required by law, PIH Health invests significant financial and other resources in efforts to improve the health of the communities it serves. When it began participating in Shaping Health, it was already developing the Health Action Lab, an umbrella collaborative that convenes nonprofits around identifying and addressing community needs and reducing health disparities.

“By the time we joined Shaping Health, in 2017, we had convened more than 60 nonprofit service and advocacy organizations that collectively agreed upon and formed four coalitions focused on areas of highest need,” said PIH Health Community Benefit Manager Roberta Delgado. “Before Shaping Health, we would have told you that we were already engaging the community because we had convened community-based nonprofits into these four coalitions—focused on chronic disease prevention and management; high school graduation rates; food insecurity; and mental health, substance abuse, homelessness, and re-entry from incarceration—to address community needs. But Shaping Health helped us recognize that what we actually had were the voices of the community filtered through the nonprofit organizations; we were missing the authentic voices that come with the participation of actual community members. Today, all four coalitions have the participation of actual community members as one of their goals—and three of them so far have been successful in bringing in that voice.”

Delgado’s PIH Health colleague, Vanessa Ivie, director of community benefit development, continued: “The primary thing we learned from Shaping Health was the value, the imperative, of opening up our decision-making processes to community members, bringing them to the table, and listening to them. Shaping Health was truly inspirational for those of us who participated in it. We set on a path to communicate what we learned about the value of social participation in health to our colleagues at PIH Health, to our Health Action Lab community partners, to everyone who feels they must have the decisions made and the details planned before presenting a program to the community. We continue to champion with them our understanding that it’s better to have community members at the table from the beginning—and it is exciting to see what happens when they embrace that.”

Today, Shaping Health exists as a voluntary practice network—17 sites in all, with some more actively connected than others—globally connecting around their diverse efforts to build social power and participation in local health systems as a key to community health improvement. In addition, via its website, Shaping Health is sharing learnings and insights about social power and participation in health far beyond its own network. TARSC is currently starting work with some of the Shaping Health participants around assessing social power and participation in health. If you’d like to know more, please reach out via the contact page on the Shaping Health website.